Sometimes, the language that shapes our identity the most isn’t our native language. Tamoha grew up speaking Bangla in her home country of Bangladesh, but began learning English at a young age in school. When she began, she never could have predicted the way that the language would have an impact on her life. By the time that Tamoha’s family moved to the United Arab Emirates, she’d been studying English for a few years; however, the education had been limited. In preparation to switch to an English immersion school, Tamoha was given a bunch of English words and asked to make sentences out of them. She recalls that the only thing she could do was make the one structure she was familiar with: “this is a bat,” “this is a tree,” and so on.

While Tamoha’s English proficiency improved dramatically alongside her increased exposure to the language in the UAE, the thing that really turned everything around for her was literature. After returning to Bangladesh as a teenager, she began immersing herself in English books—along with teenagers around the world in the early 2000s, she fell in love with the wizarding world of Harry Potter first. As she read more books in English, she also started to write her own stories. Not only did she enjoy the creative outlet, she also found that she could express herself more fully in English. Like all teenagers, she points out, she was trying to figure out who she was. The answer, it turned out, was in her language studies: “Somehow, my personality developed alongside English.”

Receiving a prize from a Sheikh at annual sports day. Abu Dhabi, UAE

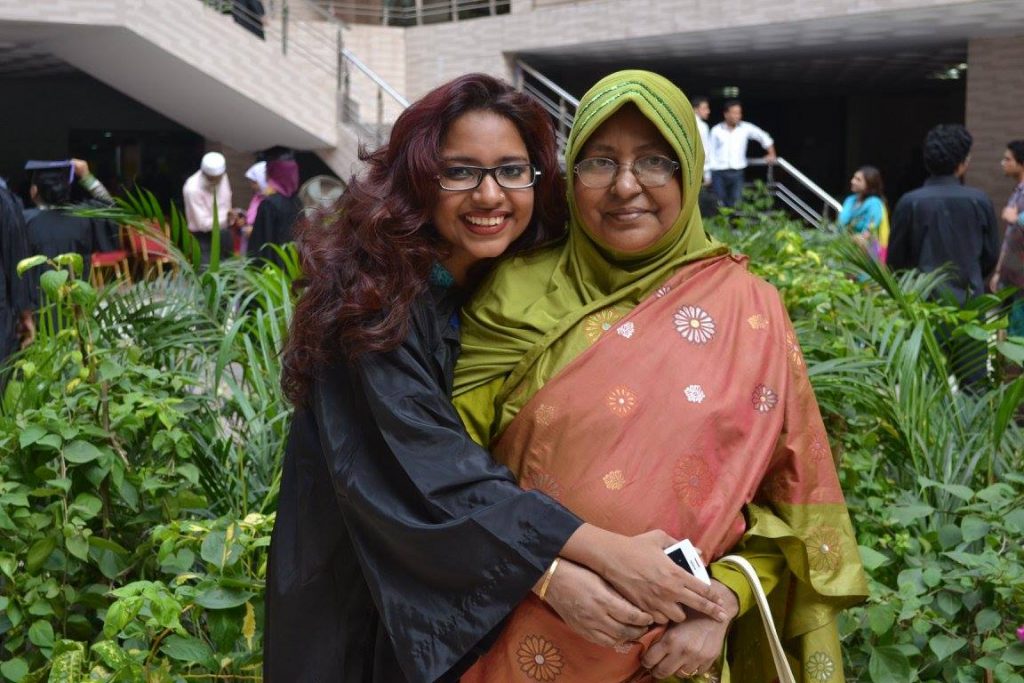

Graduating Grade X with distinction from Scholastica School, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Getting ready for a performance at school in Abu Dhabi, UAE

Eventually, poetry became the main focus of Tamoha’s writing. She founded a poetry collective at home in Bangladesh, made up mostly of bilingual poets like herself who performed spoken poetry together. Everyone approached their bilingualism in a different way—some wrote exclusively in one language or the other, while others mixed them into “Banglish.” Tamoha writes most of her poetry in English, but sometimes slips in words from her native language as well, a very intentional decision related to her history with both languages.

Although learning English has been a largely positive experience for Tamoha, she’s aware of the history of colonialism and oppression that came with the introduction of the language in her country. Poetry is one way that she chooses to reclaim the language and own it for herself. She believes that the beauty of English is that it absorbs and welcomes words—and therefore culture—from other languages, and is constantly evolving. “Language has its own life. It’s like a living thing.” To follow in this tradition, she figures that if she mixes her language into her poetry, “why can’t I get Bangla into the dictionary?”

This fall, Tamoha began a master’s program in TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) at MSU as part of the Fulbright Scholar Program. She hopes to join a poetry collective in the Lansing area to continue her passion. Though she considered studying English literature and poetry when she first began in higher education, she decided that she would rather keep it as a hobby and not risk losing her love for it by turning it into a full-time job. Instead, she chose teaching as a way to share her love of language with others.

When it came to choosing a career, Tamoha always wanted to do something that would have real social impact. The people of her country are bright, resourceful, amazing people, she says, which is why she “wanted them to have the same kind of opportunities that I got because of this language. So I thought, why not teach English?” So far, her experience teaching English has been rewarding, and she’s excited about the change the work could someday provoke. Tamoha believes that by equipping others to communicate in English—similarly to how she was helped, many years ago—more people from her country will eventually be acknowledged worldwide for their contributions to science and research. And, who knows? If Tamoha’s story is any indication, there might just be more famous Bangladeshi poets in the future as well.

– Story by Katherine Stark